World renowned pianist, silent film composer and improvisator, John Sweeney invites the TIFF audience to attend his masterclass and an extraordinary cine-concert on June 17.

It is a pleasure to have you in Cluj. How do you like it here and how do you feel about the spirit of the festival?

I’ve wandered around the centre and it’s wonderful. It’s the festival itself that amazes me… when I looked at the programme I couldn’t believe how much is in it and what an extraordinary range of films you can find. So I just think it’s a wonderful festival and clearly there’s a great audience here for that range of material.

You play in many festivals around the world. How is it to share this kind of experience to the audiences?

It’s different in each festival. There are some, for example the Giornata del Cinemamuto in Italy, which is specifically for silent films… so you have a whole audience of people who are incredibly knowledgeable about silent film. There you’re more often playing for less known films, because most of the audiences have already seen all the famous ones. At other festivals I’ve played at, where silent film is not such a big part of the festival, you’re in a way trying to convert people to it and you play the material which speaks most easily to modern audiences.

And why do you think it’s important that we keep watching silent films and we keep returning to that time period?

As you’ll see if you watch Sunrise, all the technical things which are used in modern cinema had their origins in silent film. A writer said a wonderful thing: “It shouldn’t be called early film. It should be called young film.” Because you see the excitement of people discovering new means of expression. Alfred Hitchcock, who made ten silent films before sound came in, said that silent film is the purest form of cinema because you’re telling the story only through images.

Another reason which I think is really important, particularly as we get further away from that time, is that it’s a window into the past. It was like the internet, you know? It spread all around the world. People made stuff everywhere. Sadly, a lot is lost. But a lot still survives. It’s an extraordinary kind of historical and cultural resource. What I feel very much for a silent film with a live score is that it’s a triangular thing: there’s the film, the live music and the audience.

When you are affected by the audience it’s a three-way kind of communication, so each time you play will be different. That’s another thing which I think is wonderful about silent film. Because there aren’t scores for the vast majority of silent films, the film itself could be reinterpreted through music. I’ve heard many different types of scores of the same film and you see the film differently. Sound film is a sort of object which is pretty much fixed.

Since you’re holding a masterclass in TIFF, what is the most important thing for you when you want to teach this craft?

What I’m planning to do tomorrow is to take a scene from Sunrise and go through the choices you have to make about what character you follow and how you focus on that character’s feelings, how do you structure the improvisation, how do you pace it. I’m also using various other films and I’m playing extracts from them because they also bring up different issues about how you play for a film and what you’re doing. People often think of silent film as being only the feature films in the 1920’s. But there’s so much wonderful stuff from much earlier.

I try to give a broad sense of the world of silent film and also talk about the problems we face as musicians and how we deal with those.

How did you get into film music?

I’ve always liked improvising. After I left university I got into playing for dance classes and it became a kind of mainstay. I got into silent film almost by accident. A whole lot of very early French dance films had been brought to London, so they asked me to play for them. The director of that cinema really liked it, so we started programming normal silent films. I discovered it was a whole world. Playing for the first programme of these films, half of it was very early Lumiere, which are basically documentary films, and the other half was some of the more dancey films of Georges Melies. In that first programme I ever played there was the documentary and the fantastic, the kind of two poles of what there is in film.

It’s a fantastic feeling to be involved in the whole process of bringing a forgotten film to life again.

If you could give advice to modern audiences about how they should relate to films and to film-watching, what would that be?

Go to the cinema! I think the actual communal thing of sitting in a cinema with other people, having no distractions for an hour and a half, two hours, whatever… it’s such a different experience. Quite apart from seeing it on a huge screen, I think that there’s also something unique about it. For example, if you’re going to a silent film with live music, you were either there that night or you weren’t. You know it’s never going to be the same again.

A bit like if you go to a live theatre event. So you’ve got that kind of uniqueness. I think nowadays, when so much of what we get comes from our computers, the liveness of something becomes a crucial event. You were there with an audience. It is so important. So that’s a big advice, whether it’s silent film or sound film: go and see it in a cinema! Or else there won’t be any cinemas and then we’ll all be really sad.

I have a very general question in my mind. What is music to you? What do you feel when you think about music, what does it mean to you?

Ultimately it’s a means of expression, either of yourself or… if you’re listening to other people’s music, there are things you can take from them and absorb, even if it’s not your own experience. That’s a crucial part. It could be profound, or it could be silly, or it could be all sorts of things… but it can talk. There’s a wonderful quote of the pianist and writer Charles Rosen: ”Music, of all the arts, has the most direct effect on the nervous system.”

There’s something very direct about music, whether you like it or not. It doesn’t have to be interpreted through words. People from different cultures may understand it differently, but it’s a form of art which I think is very direct. What’s wonderful to me is that it can also be a form of art which could be at the service of another art, like cinema. You can add something to the film and people may not like it, they may think you’ve changed the film, but it serves as a kind of communication between two different art forms. And I think that’s wonderful.

What is your favourite film score?

Once Upon a Time in the West. Morricone and Sergio Leone. The first ten to fifteen minutes are just the sounds creaking and all sorts of stuff… and then we have the harmonica, which only at the end we discover why. It’s got such coherence… and then there’s the murder, the whole orchestra comes… it feels like it was constructed as a collaboration.

There are so many other scores too… if you’re looking at all the classic things at the Korngold score for Robin Hood, or the Herrmann scores for lots of Hitchcock films, Elmer Bernstein scores for all sorts of things. There are loads being done now and I sometimes feel like the score is a bit of an afterthought, that the school has been just sort of stuck on. Clearly, there are also some great scores being done. But I guess if I had to choose one it would be Once Upon a Time in the West.

In the end, if you have a message or an invitation to the audiences at TIFF…

I think they’re all coming along to films so they’re doing exactly what I want them to do. Just go and see films in the cinema, or in venues… but with an audience! Also, I know it’s very easy to go to things you know you’re gonna like. But I think sometimes it’s good to go and see something you actually have no idea what it is, or you think you may not like, because often those situations where you’re surprised by things are the most interesting artistic experiences.

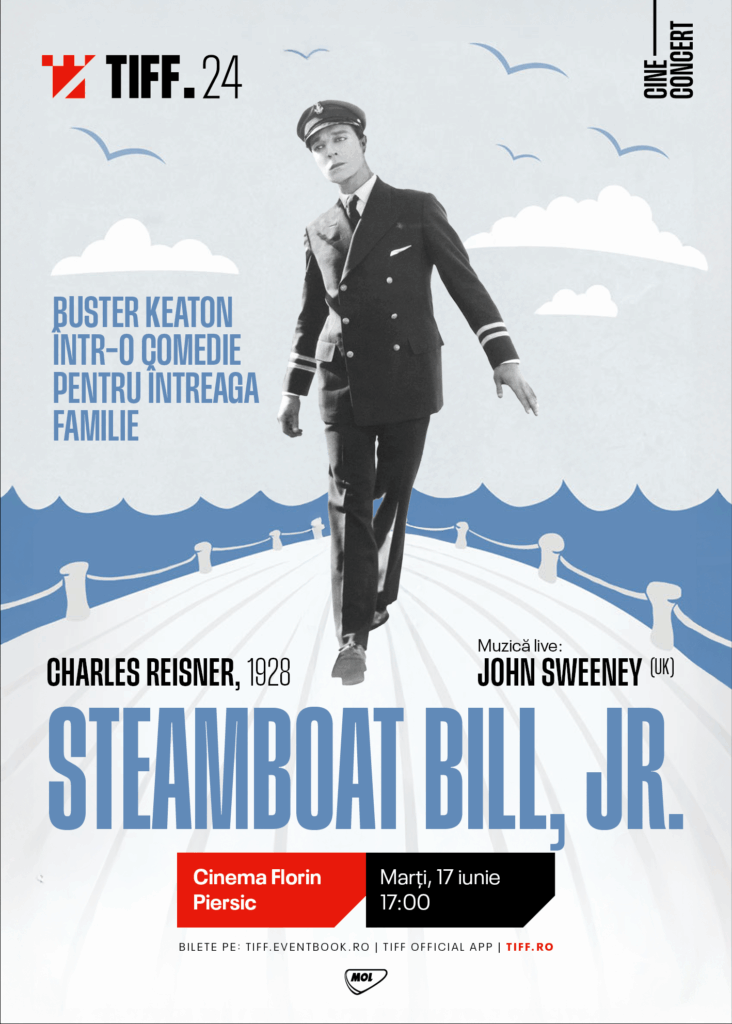

And I hope you all come along and see Sunrise and Steamboat Bill Jr. because they’re both wonderful films. Sunrise is one of the peaks of silent cinema, because it’s Murnau bringing all the sort of stuff he had built up in Germany in terms of lighting and all sorts of things, using all the resources of Hollywood to make a film which is both visually spectacular but also emotionally really powerful. And Steamboat Bill Jr. is Keaton’s finest film.

It’s got the incredible storm scene at the end that’s extraordinary and the rest of the film is also fantastic. There’s a whole father-son relationship and it’s quite powerful, because Keaton did have a difficult relationship with his father, so you get a whole sense of depth in it, as well as it being very funny. So just come along to those and come along to my so-called masterclass and ask difficult questions!

Tuesday, 17 June, 10:00 / The German Cultural Centre / MASTERCLASS

Tuesday, 17 June, 17:00 / Florin Piersic Cinema / Cine-concert STEAMBOAT BILL, JR.